In the early 2000s, specifically in the year 2020, there were two schools located in Wath-upon-Dearne: “Park Road Secondary Modern School” and “Wath Park Road Primary School.” Unfortunately, these schools were demolished by the Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council, with the intention of selling the grounds. Gleeson Builders acquired the land and proceeded to demolish these historic buildings.

In the early 2000s, specifically in the year 2020, there were two schools located in Wath-upon-Dearne: “Park Road Secondary Modern School” and “Wath Park Road Primary School.” Unfortunately, these schools were demolished by the Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council, with the intention of selling the grounds. Gleeson Builders acquired the land and proceeded to demolish these historic buildings.

The history of schools in Wath-upon-Dearne can be traced back to the 1600s. During the 1870s, many of the schools established were grammar schools, which admitted students based on an entrance test. These schools were highly respected and seen as providing great opportunities for success. They served as models for the education reforms implemented in the 1940s, which introduced a tiered structure to the educational system.

Prior to 1944, the British secondary education system was not uniformly accessible and varied greatly depending on the region. Local governments, charities, and religious foundations established schools, but access was limited, and financial support for education was inconsistent. Secondary education was primarily available to the middle class, and a small percentage of working-class 13-year-olds were still attending school in 1938.

Under the prevalent system during the Conservative governments of 1951 to 1964, students were assigned to different types of schools based on their performance in either the 11-plus or the 13-plus examination. However, the Labour government actively discouraged this system after 1965, and it was officially abolished in England and Wales in 1976, paving the way for the comprehensive system.

A secondary modern school was a type of secondary school that existed in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland from 1944 until the 1970s under the Tripartite System. This system, based on the Education Act of 1944 and the Education Act (Northern Ireland) of 1947, categorized state-funded secondary education into three types of schools: grammar schools, secondary technical schools, and secondary modern schools. However, not all education authorities implemented this system, and many only maintained grammar and secondary modern schools.

The Education Act of 1944 brought significant changes to the educational landscape. It divided the elementary sector (ages 5-14) into primary (ages 5-11) and secondary (ages 11-15) education, abolished fees for state secondary schools, and introduced more equitable funding systems. The act also renamed the Board of Education as the Ministry of Education, giving it increased authority and resources. Although the act defined the school leaving age as 15, it allowed the government to raise it to 16 when feasible, a change that was implemented in 1973.

The act also mandated local education authorities to provide school meals and milk. Free school milk was provided to all children under 18 in maintained schools starting from August 1946. However, in subsequent years, free milk was gradually withdrawn from older children. In 1968, free milk was removed from secondary schools for children over eleven, and in 1971, Conservative Margaret Thatcher withdrew free school milk from children over seven, earning her the nickname “Thatcher, the Milk Snatcher.” In 1977, Shirley Williams withdrew free milk for children between seven and five.

Wath Secondary School opened its doors on September 17, 1923, with Alderman Talbot presiding over the ceremony. Initially, the school was temporarily housed in Park Road Infants School, led by Head teacher Rev A T L Greer and three assistant teachers. The school began with 77 children and grew to 520 students over the next six years. Due to its increasing student population, the school had to expand beyond its temporary accommodation and utilize various locations, including local churches and the Wath Mechanics Institute.

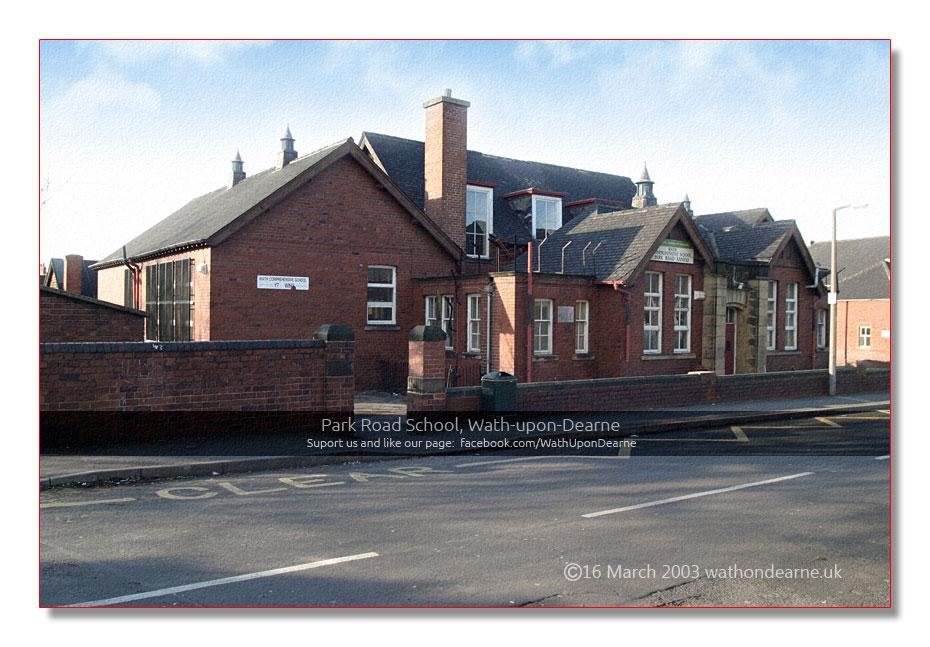

Wath (Park Road) Secondary Modern School, previously known as Wath Park Road Council School in the 1930s, operated as a secondary modern school in Wath-upon-Dearne until its closure in December 1963. The neighbouring Wath Grammar School absorbed its students, resulting in a rise in enrolment to 1491 students. The old building of Park Road Secondary Modern School became Wath Grammar School’s second site, initially serving as the basic wing for former secondary modern students. Later, it functioned as Wath’s first form (later Year 7) wing until its demolition in 2005.

Adjacent to Wath (Park Road) Secondary Modern School was Wath Park Road Primary School, a community school that catered to children aged 3 to 7. The head teacher at the time was Mrs. N. Trickett, and the school had nursery classes. However, the school closed on September 12, 2005, due to an amalgamation or merger with another establishment. Its closure was part of the larger redevelopment project undertaken by Gleeson Builders, who aimed to construct affordable housing on the site.

Looking at the implemented school systems, there are areas where constructive criticism can be offered for the betterment of education in the United Kingdom. The tripartite system, with its division into grammar, technical, and secondary modern schools, created a hierarchy that often led to unequal opportunities for students. The allocation of students based on examination results resulted in limited access for some and reinforced social divisions. The comprehensive system, which replaced the tripartite system, aimed to provide equal opportunities to all students. However, challenges remain in ensuring that students receive the necessary support and resources to thrive in a diverse educational environment.

Moreover, the withdrawal of free milk from older students caused controversy and sparked debates about the provision of essential resources for children’s well-being and development. It is important for policymakers to consider the potential impact of such decisions on students from different socioeconomic backgrounds.

In terms of infrastructure, the demolition of historical school buildings, like the ones in Wath-upon-Dearne, can be seen as a loss of cultural heritage. Preserving and repurposing historic buildings could provide unique learning environments and foster a sense of connection to the past.

To improve the educational system in the United Kingdom, it is crucial to prioritize equal access to quality education for all children, regardless of their background. This includes addressing disparities in resources, investing in teacher training and development, promoting inclusivity and diversity in the curriculum, and creating supportive learning environments. Additionally, preserving historical buildings and incorporating them into educational spaces can help instil a sense of pride and identity in students.

As we reflect on the story of the schools in Wath-upon-Dearne and the educational systems of the past, it’s evident that there is always room for improvement. Education is a vital aspect of society, shaping the lives of individuals and communities. It is a subject that sparks diverse opinions and ideas.

We invite you, the reader, to join in and share your thoughts, experiences, and insights. Your valuable input can enhance the conversation and inspire others. Perhaps you have a personal story about education, a perspective on the challenges faced by students and teachers, or innovative ideas for creating a more inclusive and effective educational system.

Your contributions can spark inspiration and offer fresh perspectives, helping us collectively explore new approaches to education. So, let your voice be heard and contribute to the dialogue. Together, we can work towards a brighter future for education, ensuring that every child has the opportunity to thrive and succeed.

Editor’s Comment:

The story of the schools in Wath-upon-Dearne provides a glimpse into the evolving landscape of education and the impact it has on communities. It reminds us of the importance of preserving history and learning from the past as we shape the future of education. The struggles and triumphs experienced by students, teachers, and policymakers serve as valuable lessons that can inform our present-day efforts to provide quality education for all.

As we delve into the complexities of education systems, it becomes evident that there are no easy solutions. It requires collective engagement and a diversity of perspectives to address the challenges and create positive change. The call to action is clear: let us come together, share our ideas, and inspire one another to make education a transformative force in the lives of children and society as a whole. By embracing collaboration and continuous improvement, we can pave the way for an inclusive and equitable educational journey for future generations.